1472

Historical Notes

The first Monte Pio

The first Monte di Pio, or Monte di Pietà, was established on 27 February 1472 by resolution of the General Council of the Republic, for the purpose of providing charitable loans to “poor or miserable or needy persons” at a minimal interest rate. By origin it is a fully secular institution, authorised from the beginning to charge an interest rate of 7.5%, thus not aspiring to any kind of speculation, but also avoiding having to make the interest-free loans recommended by the Franciscan Friars Minor, who supported the Monte dei pietà. “Monte” (“heap”) in this case indicates a collection of money, offered or deposited and then distributed for purposes of welfare or charity.

But the word had other meanings too, always connected with an idea of union or accumulation. For instance, the hereditary governing bodies – the protagonists of Sienese political life from the fourteenth century onwards – were called “Monti,” with the addition of a specific term to distinguish them from the other associations: Monte dei Gentiluomini, (Union or Group of Gentlemen), Monte dei Nove (Group of Nine), Monte dei Dodici (Group of Twelve), and so on. The Monte dei Gentiluomini united the families of the landed aristocracy of Siena who, as early as the thirteenth century, had undertaken a profitable business in trade and in particular in the movement of money, developing the custom of “letters of exchange” and “warehouse warrants”. From the fairs of Lagny-sur-Marne, Bar-sur-Aube, Provins, Troyes and Saint-Germaindes- Prés, the Sienese mercantile companies of the Ruggieri, Angiolieri, Tolomei and Gallerani families ventured out along the roads of the great European markets, lending money to princes and prelates and becoming collectors of papal tithes – bankers of the Roman Curia like the Buonsignori – or contractors of imperial duties, like the Salimbeni.

The birth of Monte dei Paschi

A courageous resistance was not enough to save the ancient republic of Siena from the allied armies of Emperor Charles V and the Florentine Duke Cosimo de’ Medici, who, after a long war, in 1557 was awarded the ancient state of Siena as a feudal domain. The Sienese were able to maintain some of their ancient magistracies, which had governed the republic for centuries, and their request to allow the Monte Pio to resume activity was also granted; on 14 October 1568, it was given a new charter similar to that of Florence’s Monte di Pietà. The Monte Pio’s account books bear witness to the progressive development of agricultural and land credit and interest-bearing loans.

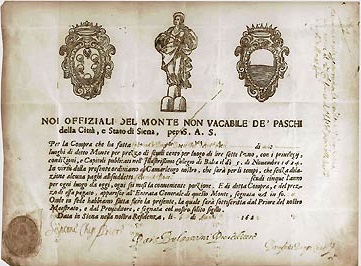

In 1580, when it assumed the task of collection agency for the Ufficio dell’Abbondanza (the food authority), the Monte Pio confirmed its role as a public bank. The conviction that the charitable works of the Monte Pio had to be expanded led the citizens of Siena to request the creation of a new credit institution that could furnish financial support to the city’s faltering economy. In particular, the new bank would assist the farmers and livestock raisers, as well as some city institutions, permitting also forms of deposit of private capital. The Grand Duke granted the request, but on the condition that the new bank be guaranteed by a lien on income from the public pasture lands in the Maremma. In 1624, then, the new institution was founded, which was to be managed by eight citizens belonging to the nobility. The revenues from the pasture lands in Maremma, called the “Dogana dei Paschi” (from which the name “Monte dei Paschi” derives), were divided into portions worth 100 scudi each, to be issued in the form of bonds guaranteeing an annual return of 5%.

The Lorraine reform

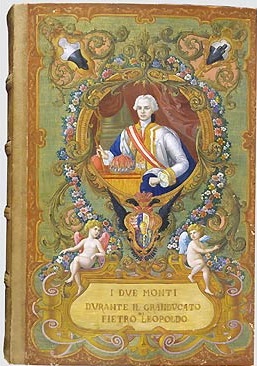

In the final period of the government of Gian Gastone de’ Medici, the administrations of Monte dei Paschi and the Monte Pio suffered significant financial problems. But with the death of Gian Gastone in 1737, the Medici line died out, and Tuscany passed under the House of Lorraine, who infused new energy into the bank. With the edict of 1759, the potential of the Monte was increased, but at the same time its administration was subjected to government control. In these years, the Monte often had difficulty responding to the growing requests for loans, given that the sale of its bonds could not exceed the limit of its guaranty fund, which more than once was increased by the government at the bank’s request.

During the twenty-five years of Pietro Leopoldo’s reign, beginning in 1765, government control of the Monte increased significantly, and in particular, in the final decade of his government the bank underwent major structural changes, the first of which was the unification – in 1784 – of Monte dei Paschi and the Monte Pio, under the name of Monti Riuniti (United Banks). Moreover, the Monte magistrates’ jurisdiction over criminal and civil affairs was definitively abolished.

Then, in 1786, it was decided that the new Sienese Civic Community would elect every three years eight Deputies – i.e., managers – of the Monti Riuniti among the nobles of the city. Also in the Deputation was the Superintendent or Provveditore, who was already nominated by the sovereign. Almost all members of the local landed aristocracy, these Sienese nobles never lost sight of the ties between the Monti and the territory and institutions of Siena. The Monte frequently made charitable contributions, deliberated in order to deal with problems outside the normal routine, such as the disastrous earthquake that struck Siena on 26 May 1798.

The bank in ninetheenth and twentieth centuries

After the fall of Napoleon and the resulting restoration of the Lorraine dynasty, the Monte had to undergo a complete reorganisation which led in 1833 to the establishment of a savings bank. In 1872, a new charter reiterated that the Monte was “an institution of the city of Siena”, therefore the Commune was charged with its “superintendence, direction and protection”. It was established on that occasion that at least half the bank’s net profits would be earmarked for augmenting the Monte’s reserves and property, while the rest could be “distributed in works of charity and public utility for the city of Siena.”

The new charter also favoured the development of the granting of farm loans, assumed in 1870 by the savings bank, which was authorised to issue Agricultural Bonds, used by the public for many years as a real currency. Monte dei Paschi managed to pass through the end-of-the-century banking scandals unharmed, and in 1910 it was in second place in Italy among savings banks, with branches in Florence, Livorno, Lucca, and seventeen other cities. The bank’s progressive expansion led to the recognition of its status as a publicly controlled corporation with the legislative decree of 12 March 1936. The new charter partially cancelled the City of Siena’s prerogative to name all the administrators of the bank and suppressed the savings bank and the Monte Pio, which were absorbed into the bank itself. In 1995, by decree of the Minister of the Treasury, the banking firm was transformed into a corporation called Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena. Since June 1999, Banca Monte dei Paschi shares are traded on the Mercato Telematico Azionario (screen-based trading market) of the Italian Stock Exchange.

In 2017, following a capital increase of Euro 8.3 billion, the Italian State became the bank’s majority shareholder.

1624

1907-1930

1936

1946-1989

1990-1994

1995

1999

2000-2005

-

Acquisition of participation in some regional banks with deep roots in their own territory, such as the Banca Agricola Mantovana;

-

Reinforcement of the structures of production in strategic market segments through the development of product companies: Consum.it in the sector of consumer credit, MPS Leasing and Factoring in the parabanking sector, MPS Finance in investment banking, MP Asset Management SGR in managed savings, MPS Banca Personale in financial promotion; Concentration in MPS Banca per l’Impresa of the activities in the sector of specialized credit to businesses and of corporate finance services;

-

Development of commercial productivity, with the aim of improving the level of assistance and consultancy to investors and businesses, through service models specialized as to segment of the clientele;

-

Consolidation of activities in certain areas of strategic importance, such as private banking markets, and, following pension reform, that of private pension plans;

-

Implementation of a vast program of opening new branches of the Group, with the goal of a network of more than 2,000 branches by the end of 2006

2008

2014

Founding of Widiba, the Group’s online bank which, with its highly innovative technology platform and the professional advice of Personal Advisors, combines listening and attention to build deep and long-lasting relationships. Widiba made its debut on the market in September 2014, after a year of collaborations with more than 150 thousand users who gave a concrete contribution to its creation: from designing and choosing the name (WIse-DIalog-BAnk) to proposing a total of 3,500 ideas which have turned into services and products that are offered to our customers.

2017

Following a capital increase of Euro 8.3 billion, the Ministry of Economy and Finance became MPS’s majority shareholder. At the same time, the bank began a process of radical transformation geared towards innovation, the rationalisation of resources and bringing the customer back to the core of its business.